Born in Heilongjiang Province in 1966

Graduated from the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts in 1991, Sichuan, China

Currently lives and works in Beijing

SELECTED COLLECTIONS

Denver Art Museum

Institut Valencia d’Art Modern (IVAM), Valencia, Spain

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK

Artium, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain

J. Paul Getty Museum, USA

National Gallery of Victoria, Australia

Hammer Museum

San Diego Museum of Art

Board Member of Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA

Billstone Foundation, Spain

Aspen Art Museum

Williams College of Art, USA

MUMOK, Austria

New Orleans Museum of Art, USA

Philadelphia Museum of Art, USA

Cisneros Foundation, Miami, USA

Board member of Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA.

Rubell collection

Mori Art Museum

Smart Museum of University of Chicago, USA

Brooklyn Museum, USA

The Moscow House of Photography, Russia

Art Tower Mito-Contemporary Art Museum, Japan

Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP), Paris, France

Guy and Miriam Ullens Foundation, Switzerland

National Art Museum of Brazil, Brazil

Oriente Foundacion, Portugal

Queensland Art Gallery, Australia

JGS Foundation, New York, USA

The International Center of Photography, New York, USA

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2016

One World, One Dream: Works of Wang Qingsong, Dirimart Gallery, Istanbul, Turkey

2015

Wang Qingsong – Everything is Possible, Gallery Of Photography, Dublin, Ireland

Wang Qingsong, Beetles & Huxley Gallery, London, UK

2014

Follow You – Wang Qingsong, Koege Museum, Denmark

One World, One Dream, White Box Art Center, Beijng, China

Asian Contemporary Photography, Wang Qingsong and Jung Yeondoo, Daegu Art Museum, Korea

AD-Infinitum, Frost Art Museum, Florida, U.S.A

2012

The History of Monuments, Taipei Museum of Contemporary Art, Taiwan

Grids Painting, Taipei Galerie Bistro, Taipei, Taiwan

Wang Qingsong, Gallery 100, Taipei, Taiwan

2011

Toward the Social Landscape, Lianzhou Photo Festival, Guangdong, China

LOOK EAST, Lucca Photo Festival, Italy

Happy New Year, Tang Contemporary Art, 798 Art District, Beijing, China

History of monuments, Les Rencontres d’Arles, France

When the World Collides, International Center of Photography, New York City, USA

2010

Follow Me, Centro Andaluz de la Fotografia, Almeria, Spain

Wang Qingsong: Three Video Projects, Pékin Fine Arts, Beijing, China

Wang Qingsong – Fotografie, Stadtmuseum, Siegburg, Germany

2009

Wang Qingsong, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, USA

2008

Wang Qingsong, Albion Gallery, London, UK

Caution, PKM Gallery, Beijing, China

Phantom China, Kunsthalle Nexus, Saalfelden, Austria

Wang Qingsong – Temporary Ward, Baltic Contemporary Art Center, Gateshead, UK

Wang Qingsong Solo Show – Panic, Fear and Violence, Marella Gallery, Beijing, China

Unparalleled Madness, Madhouse Contemporary, Hong Kong

2007

China: Past, Present & Future, MEWO Kunsthalle, Memmingen, Germany

Thinker – Wang Qingsong Solo Exhibition, Chinablue Gallery, Beijing, China

Wang Qingsong, PKM Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Wang Qingsong: Between Nostalgia and Cynicism, Espaço Cultural Contemporâneo (ECCO), Brasilia, Brazil

2006

Wang Qingsong, Albion Gallery, London, UK

2005

Wang Qingsong in Arras, City Hall, Art Academy and Public Library, Arras, France

2004

Wang Qingsong – Romantique, Salon 94, New York, USA

Wang Qingsong – Romantique, Courtyard Gallery, Beijing, China

2003

Wang Qingsong: Present-day Epics, Saidye Bronfman Contemporary Art Center, Montreal, Canada

2002

Wang Qingsong Photography, Foundation Oriente, Macau

Golden Future – Photography by Wang Qingsong, Galerie Loft, Paris, France

Wang Qingsong, Marella Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy

Satirizing the times, 2nd Pingyao Photo-Festival, Pingyao, China

2001

Glorious Life – The Photographs of Wang Qingsong, Wan Fung Gallery, Beijing, China

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITION

2016

China Whispers, Kunstmuseum Bern, Switzerland

12th edition of Dakar Biennale, IFAN African Art Museum

Silk Road of the Images: Tianshui Photography Biennale, Gansu Province, China

“ID”, Seoul Lunar Photo Festival, National Palace Museum of Korea in Gyeongbokgung Palace

Historicode – Scarity and Supply, the 3rd edition of Nanjing International Art Exhibition, Art 100 Lake Museum, Nanjing, China

2015

Sudden Enlightening – Comparative Research Exhibition on Sino-German Conceptual Art, Harmony Museum, Wuhan, China

Fairy Tales, video festival with public delivery, Taipei Moca

Fusion: Chinese Modern and Contemporary Art since 1930s, Wan Lin Museum, Wuhan, Hubei, China

Works in Progress//Photography in China 2015, Folkswang Museum, Essen, Germany

Unveiling Fundamentals in Contemporary Art through Asia, OHD museum, Indonesia

Worlds in Contradiction – Areas of Globalization, Galerie im TaxiPalais, Austria

China 8, Folkswang Museum, Essen, Germany

Interlocking Strategems, Xi’An Art Museum

Dali International Photography Festival, Yun’Nan Confucius Temple, China

From Grains to Pixels – Contemporary Photography from China, Shanghai Center of Photography, China

Unfamiliar Asia: 2nd edition of Beijing International Photography Biennale, CAFA Art Museum

Seeing the Sky from a Fabricated Scenario — 1st Xi’An Photography & Video Literature Art Exhibition, Xi’An Art Museum, China

Re-Imaging – Experimental Field of the Light, Hubei Art Museum, China

2014

Flux realities : a showcase of chinese contemporary photography, 4th Singapore International photography festival, Singapore

Liquid Times, Seoul Art Museum, Korea

China Arte Brasil, G11, Sao Paolo OCA Exhibition Center, Brazil

China-Portugal Contemporary Art Exhibition, Beijing Millennium Art Museum, China

Artists from Binghe Compound Apartments, Songzhuang Art Museum, China

Advance through Retreat, Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, China

Origins, Memories and Parodies, Daegu Photo Biennale, Korea

Art Festival Watoum Collected Stories #6, About small happiness in times of Abundance, Belgium

Ostrale ’14, Dresden, Germany

Seeing the Unseen: Photography and Video Art in China Now, The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, State Art Museum of Florida, U.S.A

12th China Art Works Experimental Art Exhibition, Today Art Museum, Beijing

Contemporary Photography in China from 2009-2014, Minsheng Modern Art Museum, Shanghai

3rd Wuhan Art Literatures Exhibition, Hubei Art Museum, China

2013

Transfiguration, Venice Biennale, China

Mum! Am I Barbarian?, Istanbul Biennial, Turkey

Cold View-Wang Qingsong, Wang Zhiping, Lu Di and Pan Yue, Guangdong Art Museum, China

Aura and Post-Aura, First Beijing International Photography Biennial, the Altar of Millennium in China, Beijing

Spectacle Reconstruction – Chinese Contemporary Art, MODEM Centre for Modern and Contemporary Art, Hungry

2012

A History of Chinese Contemporary Photograhy, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Brussels, Belgium

Go Figure ! Contemporary Chinese Portraiture, National Portrait Gallery, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Canberra, Sydney, Australia

CAPITAL – Merchants in Venice and Amsterdam, Swiss National Museum, Zurich, Switzerland

Beyond the Wall, Jeonju Photo Festival, Korea

The Best of Times, The Worst of Times: Rebirth and Apocalypse in Contemporary Art – First Kyiv International Contemporary Art Biennale, Kyiv, Ukraine

Perspectives 180: New Video From China, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH), Houston, U.S.A

2nd Western China International Art Biennale, Yinchuan Art Center, Ningxia, China

3rd Singapore International Photo Festival, Singapore Management University

2011

Living, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark

43rd Recontres de la Photographie, Arles, France

Monanism, Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania, Australia

Surreal versus Surrealism in Contemporary art, Institut Valencia d’Arte Moderna (IVAM), Spain

Towards the Social Landscape, Lianzhou Photo Festival, Guangdong Province, China

2010

Beauty of Distance: Songs of Survival at a Precarious Age, Sydney Biennale, Australia

Daegu Photo Biennale, Korea

International Contemporary Art Biennale in China West, Tianye Contemporary Art Museum, China

Photography from the New China, Getty Museum, Los Angeles, USA

2009

Action – Camera: Beijing Performance Photography, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada

Three Decades: The Contemporary Chinese Collection, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia

China: Contemporary Art, Centro Hispanoamericano de Cultura, 10th Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba

The 3rd Guangzhou International Photo Biennale, Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, China

The Simple Art of Parody, Taipei MOCA, Taiwan

Gextophoto 2009 International Photography Festival, Gexto, Spain

The V VentoSul Biennial: Large Water: Maps Altered, Brazil

The Dark Science of Five Continents, Gallery BMB, Mumbai, India

Experimental Cases of Contemporary Chinese Art, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, China

Mise-en-Scene, Officina, Beijing, China

2008

CINA XXI Secolo. Arte fra Identita’ e Trasformazione, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, Italy

Fabricating Images from History, Chinablue Gallery, Beijing, China

Body Language: Contemporary Chinese Photography, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

55 Days in Valencia – Chinese Art Meeting, Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno (IVAM), Valencia, Spain

China Gold, L’Art Contemporain Chinois, Musee Maillol, Paris, France

Adidas Sport in Art Exhibition, Today Art Museum, Beijing, China

Go Game, Beijing!, German Embassy, Beijing, China

Translocalmotion: 7th Shanghai Biennale, Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, China

Expenditure, Busan Biennale 2008, Busan, Korea

21: Selections of Contemporary Art at the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA

Christian Dior and Chinese Artists, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, China

China: Construction and Deconstruction, MASP, San Paolo, Brazil

2007

Zhu Yi! Chinese Contemporary Photography, Centro-Museo Vasco de Arte Contemporaneo, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain

Timer – Intimita/Intimacy, Triennale di Milano, Milan, Italy

Thermocline of Art, New Asian Waves, ZKM – Museum of Contemporary Art, Karlsruhe, Germany

Timeline: Human Speed & Technology Speed, Korea Center, Beijing, China

Beyond Icons – Chinese Contemporary Art, Miami Design District, Miami, USA

Mirror Image of Diversity – Six Person Exhibition of Contemporary Art, Beijing Tokyo Art Projects, Beijing, China

2006

Moscow International Photo Biennale, Moscow House of Photography, Moscow, Russia

2nd Bucharest Biennale, Bucharest, Romania

Public Image, public project in the city of Liege, Belgium

Acting the Part – Photography as Theatre, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver

The 37th Rencontres d’Arles Photographie, Arles, France

C on Cities – The 10th International Venice Architecture Exhibition, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy

Ecotopia, International Center of Photography, New York, USA

Intersections – Shifting Identity in Contemporary Art, John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Wisconsin, USA

2005

Re-viewing the City – the 1st Guangdong International Photo Biennale, Guangdong Museum of Art, China

Over One Billion Served, Singapore Civilizations Museum, Singapore

1st Biennale Internationale d’Art Contemporain Chinois de Montpellier, Montpellier, France

Follow Me! Chinese Art at the Threshold of the Millennium, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

Die Chinesen, Museum Het Kruithuis, Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands

Beyond Delirious: Architecture in Selected Photographs form the Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection, Miami, USA

Baroque and Neo Baroque – The Hell of Beauty, Domus Artium 2002, Salamanca, Spain

Always to the Front – Chinese Contemporary Art, Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan

Grounding Reality – Chinese Contemporary Art, Seoul Art Center, Seoul, Korea

2004

Over One Billion Served, Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver, USA

Photosynkyria 2004 – Photography as Narrative Art, Photography Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece

Officina Asia (Asian Workshop), Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Bologna, Italy

Image of History, Photo Espa�a, Madrid, Spain

Between Past and Future, International Center of Photography, New York, USA

Die Chinesen – Contemporary Photography and Video from China, Wolfsburg Museum, Wolfsburg, Germany

Exposure, Hereford Photo Festival, Hereford, UK

Past in Reverse – Contemporary Art of East Asia, San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, USA

2003

First Prague Biennale, Prague, Czech Republic

Fashion and Style , Moscow House of Photography, Moscow, Russia.

A Strange Heaven – Contemporary Chinese Photography, Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague, Czech Republic

Noorderlicht Photo Festival, Groningen, the Netherlands

2002

Run, Jump, Climb, Walk, Yuanyang Art Center, Beijing, China

Money and Value – The Last Taboo, exhibition in the framework of Expo 02, Biel, Switzerland

Special Projects, P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, New York, USA

Chinese Modernity, Museum of the Foundation Armando Alvares Penteado (FAAP), S�o Paulo, Brazil

The 2nd Pingyao International Photography Festival, Pingyao, China

Paris-Pekin, Espace Cardin, Paris, France

CHINART – Contemporary Art from China, Museum Küppersmühle, Duisburg, Germany

2001

Constructed Reality – Beijing/Hong Kong Conceptual Photography, Hong Kong Arts Center, Hong Kong, China

Next Generation – Art Contemporain d’Asie, Passage de Retz, Paris, France

Promenade in Asia – CUTE, Art Tower Mito, Tokyo, Japan

Chinese Album, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Nice, France

Cross Pressures, Finnish Museum of Photography, Helsinki, Finland

Asian Contemporary Art Exhibition, Guangdong Museum of Art, China

2000

Man and Space – 3rd Gwangju Biennale 2000, Gwangju, Korea

Big Torino 2000 – Biennale Arte Emergente, Turin, Italy

China Avant-garde Artists Documents, Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka, Japan

Unusual & Usual, Yuangong Art Museum, Shanghai, China

1999

Ouh La La, Kitsch!, TEDA Contemporary Art Museum, Tianjin, China

SYNERGI: Fourteen Danish and Foreign Artists Exhibition, Udviklings Center Odsherred, Copenhagen, Denmark

1998

Site of Desire: Taipei Biennial, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

1996

China!, Kunstmuseum Bonn, Bonn, Germany

Gaudy Life, Wan Fung Art Gallery, Beijing, China

HISTORY OF MONUMENTS

As China Evolves, So Does an Artist

by Karen Rosenberg

The New York Times, January 27th 2011

“Competition” (2004) is one of 15 works in the exhibition “Wang Qingsong: When Worlds Collide” at the International Center of Photography.

The Beijing artist Wang Qingsong, born at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, has seen China morph from an insular, rural society to a globally engaged dynamo. His art has evolved just as rapidly, from Gaudy Painting (a Chinese variation on Pop) to giant photographs staged in movie studios and short, performance-based videos. All of these works regard recent changes in Chinese culture — the proliferation of McDonald’s, overcrowded cities, even a booming art scene — from an ironic stance that needs no translation.

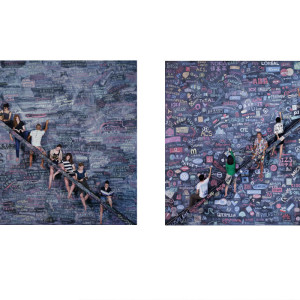

In the 2004 photograph“Competition,” for instance, he standson a ladder with megaphone in hand in front of a wall of hand-lettered advertisements, giving a Western-inflected, consumerist twist to the old Red Guard posters that adorned city walls during the Cultural Revolution. Brand names including Citibank, Starbucks and Art Basel are visible, though much of the writing is in Chinese.

That striking image is part of a small survey, “Wang Qingsong: When Worlds Collide,” at the International Center of Photography. It’s not the first appearance at the center for Mr. Wang (whose full name is pronounced wahng ching-SAHNG); he appeared in the 2004 exhibition “Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video From China,”organized jointly with Asia Society.

The current show is Mr. Wang’s biggest presentation in the United States so far, though at just a dozen photographs and three videos it’s a bit of a tease. It leaves you wanting to see more from this gimlet-eyed artist — and from the Center of Photography.

The curator Christopher Phillips, who organized the show, links Mr. Wang to Western photographers and painters like Gregory Crewdson and the Weimar-era satirist George Grosz. Other Westerners that may come to mind are Andreas Gursky, for his hyperdetailed depictions of unchecked globalism, and Thomas Demand, whose photographs of meticulously constructed paper-and-cardboard environments make fictions of “real”political events.

But it seems disingenuous to talk about the staged photograph, in this context, without acknowledging its Socialist Realist history. Government censorship is another subject left untouched in the show, even as the art world digests news about the destruction of the artist Ai Weiwei’s studio in Shanghai this month. (Mr. Wang, though less outspoken than Mr. Ai, has in the past been questioned by the police and has had negatives confiscated.)

The earliest works on view date from the late 1990s, after Mr. Wang abandoned his Gaudy Art paintings. They’re sharply observant but not very nuanced; the image of a materialist Buddha clutching cigarettes, beer and a cellphone is typical.

The humor is more sophisticated in Mr. Wang’s interpretation of the 10th-century scroll painting “Night Revels of Han Xizai.” He casts the Beijing art critic Li Xianting in the role of the debauched court official Han Xizai, and himself as the emperor’s spy. Scantily clad “courtesans” sip Pepsi and Jack Daniel’s as Mr. Wang peeks out from behind a curtain. Beyond the voyeurism there is a parable about the fate of the intellectual in contemporary China.

Almost as rich are the works from 2003-5, “Competition” among them, elaborately staged in a Beijing film studio and starring Mr. Wang. The sets are artworks in themselves, as is made clear by short behind-the-scenes videos at the photography center.

In “Follow Me” Mr. Wang sits at a desk in front of an enormous chalkboard covered in English and Chinese writing. The setup riffs on a popular BBC-Central China Television language-instruction program from the 1980s, but the words and phrases being taught here seem to have more to do with the millennial art boom; they include “Documenta”,“Venice Biennale” and “Uli Sigg,” the major Chinese-contemporary collector.

Other works offer wry commentary on the fast-tracked development of Chinese cities and the plight of the migrant workers who come from rural areas to build them. In the most recent of these images, “Dormitory” (2005), dozens of nude figures inhabit small compartments in what is essentially a giant bunk bed constructed by Mr. Wang. Curiously, some of them seem to be occupied by artist models (note the seated figure plucked from Man Ray’s “Ingres Violin,” one of many Western art references in Mr. Wang’s photographs).

Just as he shifted from painting to photography Mr. Wang has lately turned to video, making short works that, in a familiar YouTube idiom, compress lengthy or difficult endeavors into just a couple of minutes. Some of them pick up on the urban themes in the photographs; for “Skyscraper” Mr. Wang hired construction workers to erect a 115-foot golden scaffold on the outskirts of Beijing.

Others, though, are more performance oriented. In “Iron Man,” for instance, the artist is pummeled bloody by spectral fists. The work’s title, in Chinese, describes positive attributes of ambition and endurance. Westerners, though, are likely to perceive the violence as a dark meditation on human-rights abuses — notwithstanding Mr. Wang’s broad grin at the end of the video, or his vague comments on the wall label. “We all get hit in one form or another in life,” he says, “perhaps not literally but figuratively.”

Violence also dominates “123456 Chops,” in which Mr. Wang’s younger brother hacks a goat carcass into minuscule pieces on a wooden platform. It’s a spectacularly grisly version of process art.

If the videos are any indication, Mr. Wang is moving from critiques of materialism to more subversive topics and from Hollywood-style set design to stripped-down, bodycentric actions. His art is getting tougher as it gets lighter.

Wang Qingsong’s photographs

by Via Prospero

More Intelligent Life, 2011

Wang Qingsong’s photographs are darkly humorous. Staged and absurd, they tend to consider the hollow promises of consumer culture in China. In “Bathhouse” (2000), for example, the artist sits in a pool surrounded by plastic fruit, Coca-Cola bottles and painted ladies, all of whom look terribly bored (pictured below). Later works are both grander and more subtle, such as “Yaochi Fiesta” (2005), a mythical scene of paradise in which scores of nude Chinese look uneasy, even ashamed. With legs crossed and mouths pursed, they appear chagrined by what was meant to be a delicious fantasy. Mr Wang, a Beijing-based artist, arranges these scenes in a warehouse-like film studio. Though often amusing, they are more than mere gags. Rather, they often feel like odd group portraits, with plenty of powerful reasons to keep looking beyond the first snigger.

This wry approach to chronicling Chinaʼs economic and cultural changes is earning international notice. “Wang Qingsong: When Worlds Collide”, his most extensive solo show in America, has just opened at the International Centre of Photography (ICP) in New York. His work is also part of “Photography from the New China”, now at the Getty Centre in Los Angeles. Mr Wang, at the opening of his show at the ICP, expressed gratitude for the attention. “Going overseas is like opening a door to what is happening in the West,” he told The Economist (in a conversation translated by his wife, Zang Fang). “In China we canʼt see whatʼs going on in the world.” Time in the West, and perhaps especially in America, helps to clarify for Mr Wang some fundamental cultural misunderstandings. “China in the Western idea is like a tiger—a danger, a threat,” he said. “But maybe China is just a big rhino, gentle and harmless. Not a monster.”

Mr Wang conceded that it is “tricky” to be an artist in China, where “the best student is the best follower”. Like Ai Weiwei, a Chinese artist whose studio was recently demolished by government authorities, Mr Wang suggested that artists are duty-bound to pose questions in the face of Chinaʼs cultural uniformity. “We should be suspicious of what is real and what is false,” he said. “We must make our own judgment.”

Indeed, there is a palpable bitterness in Mr Wang’s work, which often features corporate logos and vacant faces. In China, where Mao and his Cultural Revolution destroyed centuries of tradition, the newly prosperous are filling this cultural void with new material pleasures. Mr Wang depicts his unsophisticated countrymen in a thrall to empty, tacky consumerism, embracing McDonald’s and Jack Daniels as signs of progress. He seems to lament not only the vulgar exports of the West but the way Chinese people gobble them up—a relationship he once described as a “mutually beneficial conspiracy”. “When McDonaldʼs came to China, it opened in the fanciest parts of Beijing, so people assume this is nice cuisine from the West,” Mr Wang recalled. Thousands of people rushed to eat burgers and many still hold swanky parties at the outlets. The artist seems pained by this misunderstanding, admitting that it was only years later that he himself learned that McDonaldʼs was nothing but a fast-food chain.

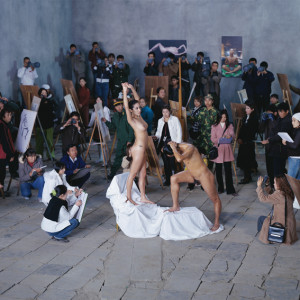

Trained as a painter, Mr Wang moved to photography in the mid-1990s, believing it was a better way to document Chinaʼs dynamism. “Night Revels of Lao Li” (2000) is Mr Wangʼs interpretation of a famous tenth-century scroll painting by Gu Hongzhong. The original, called “Night Revels of Han Xizai”, follows a frustrated court official who resorts to debauchery after he realises his reform efforts are falling on deaf ears. It is a painting that captures the uneasy role of intellectuals in Chinese society. Mr Wangʼs contemporary version (detail above) features Li Xianting, a Beijing art critic, who government officials had shoved from his post as editor of an influential magazine. The triptych sees Mr Li surrounded by dowdy concubines and shabby pleasures, little of which seems enviable. “After so many years of Chinese history, I find no change in the destinies of intellectuals in China,” Mr Wang has said of this photograph. “ After the feast is over and the guests are gone, the intellectual is very sad.”

Wang Qingsong Interwiev

by Danielle Shang

YISHU, September 2011

S: I have seen many versions of your biography; they are all slightly different. I want to for once get the correct information from you.

W: I was born in Helongjiang in 1966. My family moved to Hubei province, when my father was transferred to an oilfield there in 1969. After he passed away in 1980, I replaced him to work on a drilling platform. In 1990, I went to Sichuan to attend preparation classes for the art academy. I was admitted by Sichuan Art Academy the following year and graduated with an associate degree in oil painting in 1993, when I immediately moved to Beijing.

S: When you worked in the oilfield, how did you hear about Western contemporary art and Chinese avant-garde art movement?

W: Hubei was very progressive in the mid 1980s. Many young artists from Hubei participated in the ‘85 New Wave (1). I learned about contemporary art from my friends. There were three important art publications at the time that also spread the news: Fine Arts, Jiangsu Art Journal and Art Newspaper (2).

S: In most of your work, you illustrate the diligent pursuit of personal dreams and the uncertain outlook of the future in big cities of China against the background of globalization and modernization. How was your experience of pursuing your own personal dreams? What were your dreams when you came to Beijing? You considered yourself a “loser.” Why?

W: I took my father’s place on a drilling platform. Even though I enjoyed drilling, but I was very aware that the job had a low social status. People looked down upon workers on the oil fields. I was not good at schooling either. I took the admission exams for the art school for five times before I was finally accepted. I had failed so many times in my life before I moved to Beijing. I couldn’t even go back to the oilfield to work in a more decent department, after I graduated. When I came to Beijing, my dream was to eventually enter a national exhibition.

S: You were part of Gaudy Art. Why were you interested in that style?

W: Gaudy Art was inspired by pop culture. I was fascinated with pop culture at that time. I realized at the time that our tradition needed to be synchronized with our contemporary life. Gaudy Art was an attempt to digest. But the other reason was that in the ‘90s, Political Pop and Cynical Realism were already very popular. Wang Guangyi, Fang Lijun and Yue Minjun had a fast and stellar rise. In 1993 and 1994, Fang was invited to participate in the Venice Biennale and San Paolo Biennale. It was not cool to be a follower. I saw no hope for imitating their styles. I actually wanted to quit painting all together.

S: While living in Yuanmingyuan, you hang out with many artists who were also known as Gaudy Artists, such as Liu Zheng and Xu Yihui. You discussed a lot about pop culture. What was the pop culture like back then?

W: The pop culture was definitely different from the pop culture in the West. It started with music. Music was changing in the ‘90s. Many propaganda songs, that once were political and serious, were rearranged to become pop songs: not the pop songs for the middle class or city folks, but folk songs for peasants and truck drivers. The conversion made it easy for ordinary people to digest “high” culture. The repackaging also achieved a commercial success. Many songs about Mao sung by girls with coy voices became instant hits.

S: How was it like to live in Yuanmingyuan and later Song Zhuang?

W: In Yuanmingyuan, it was about survival. The living condition was primitive. Most of us were outsiders of society. Nobody had a steady income or a stable job. A few people hung out in Yuanmingyuan because they enjoyed the Bohemian lifestyle. Song Zhuang was a scene of prosperity at that time. Yue Minjun, Fang Lijun and Liu Wei had enough money to build their own studios. I didn’t have money, so I rented a place to live in Song Zhuang, after I was forced to move five times in ‘95 and ‘96.

S: In 1996, you finally quit painting. You stated that you were unable to continue painting. What did you mean by that?

W: I hit the dead end. If I had continued painting, I would have ended up being a copycat. If you notice, at that time performance art, installation and photography also appeared in China, because we could not make painting work. I started to experiment with photography and photo collage. You can see the cutouts from magazines and calendars in my images from 1996, 1997.

S: Our Life is Sweeter than Honey (1996) and the Last Supper (1996) were all photo collage?

W: Yes. The former was made out of the propaganda poster for Hong Kong’s handover and the latter was made of a calendar: one girl from each month, plus me in the middle. Thirteen of us.

S: Were you aware that the Last Supper was from the Bible?

W: Of course. I knew it when I was taking art classes. Everyone was copying Western masterpieces and making sketches of Western statues: Caucasians with curly hair. All the art works that we studied were European church related. Such is our art education system: completely borrowed from Europe. It was first introduced to China by Xu Beihong.

S: I know that Li Xianting was influential in the ‘90s and you were friends with him. When was your first solo show? Did Li Xianting have anything to do with it?

W: My first solo show was at Ludovic Bois’ Chinese Contemporary Art in London. It was a painting show. Li was not involved.

S: I want to talk about Night Revels of Lao Li (2000). Was there a particular reason to choose Li Xianting as the protagonist? What is your experience in China as an intellectual? Do you think you are carrying out the responsibility for social reform and political progress? Or do you think that you are resigning to the state of Han Xizai (3), because you feel disappointed and powerless about China’s reality?

W: I didn’t intend to involve him. He was so famous and idolized, and I was nobody. I was actually intimidated by him. Before the photo shoot, I had a conversation with Li. When he heard about my project, his eyes were brightened. He told me that he just finished an article on the destiny of Chinese literati and Night Revels of Han Xizai. He volunteered to play the role of Han Xizai for my shooting after our talk. I originally hired someone else who had a long beard and looked very much like the figure in the original painting. But Lao Li had something that nobody had: his manner, his emotional depth and his experience in life. He was the perfect Han Xizai. After I developed the film, I was profoundly impressed with his expression of powerlessness and stoicism; it was precious. You know, what happened to Han Xizai a thousand years ago is not different from what happens to today’s intellectuals.

Li was not acting. It was his true feelings. In 2000, when Chinese government began to involve in contemporary art, many renowned artists collaborated with the government. Li never verbalized his disapproval, but I could see it on his face. Once I spent the night on the sofa at his home. He asked me: “Do you know who have slept on this sofa before? From Luo Zhongli to Fang Lijun to Wang Guangyi, they all have slept here. Now you.” His sofa was a metaphor for Chinese contemporary art scene. He saw enough of coming-and-going and was skeptical about the clueless illusion of success.

S: You sold all your paintings by the end of the ‘90s. You don’t have any paintings left, do you?

W: Technically I didn’t sell anything. Nobody bought my paintings. But I begged and added pressure to a few people to pay for my paintings, because my mom was fatally ill and I needed money for the hospital bills. In 1999, I gave three of my biggest paintings for only 10,000 RMB. I fundraised about 20,000RMB for my mom.

S: Before 2000, you could only afford to take pictures of yourself. How were you able to rent large film studios, hire numerous models and build elaborated sets after 2000?

W: Money was tight in the ‘90s. A model would cost over 100RMB, which could afford someone to live for an entire month. My mother passed away in 2000. Before her death, her working unit compensated her for some of the hospital expenses and ten-month-worth salary. She left every penny to me. I spent it all on the production of Night Revels of Lao Li, for which I began to prepare in 1998, but I kept putting it off, due to the lack of money.

S: Because you employ sprawling studio setting and stylized arrangements, you are often compared to Jeff Wall and Gregory Crewdson. I find your sensibility quite different from theirs. Their photography is sleek and polished. Many images look like still-images from big-budget movies. But yours are rough, awkward, satiric and whimsical.

W: When someone first pointed it out to me, I had no idea who they were. I looked them up. Their photography emphasizes on technique. Their work is textbook-perfect. But I don’t care about technique. If we must talk about inspiration, my work is inspired by the photography during the Cultural Revolution. Most of propaganda photos at that time were ridiculously staged. They made up hundreds of photos of a young soldier Lei Feng and they gathered crops from other farms to fill up one rice paddy field for the photo shoot of a miracle harvest under Mao’s leadership. Pictures of people reading Mao’s books in the sun are laughable. How can you see anything in the bright sun?

I was also influenced by Pierre & Gilles. I saw a postcard of their work on the street of London. I immediately detected the similar mockery and sarcasm in their work. Their photo of a tearful army official of the former Soviet Union (4) was amazing: garish, erotic and ridiculous. I later bought their books to further study their art. Their art is not exactly photography, because it involves postproduction of painting and coloring. I regard them as great artists. When they came to China to exhibit in Shanghai, we almost met. They expressed the interest in remaking one of my photographs. I liked the idea. We exchanged emails and tried to make a plan to meet, but unfortunately it didn’t happen. It was a pity.

S: Not all of your photographs have grand schemes and massive studio sets. Follow Me (2003) was simple but nevertheless striking.

W: People thought that my art attracted so much attention, because I spent so much money on big setting. So I deliberately minimized the production of Follow Me and gave myself a budget of 100 RMB. The only things that I paid for were the box of chalks and the stick in my hand. The total cost was 20RMB. I regret very much that I didn’t document the shooting. It was so messy. The floor was covered with rubbish. But after I edited the photo and cropped out the floor, it became one of my favorite works. The image was immediately embraced in the West, because of the English words on the chalkboard, which made it easier to relate. The Chinese audience prefers Night Revels of Lao Li.

S: Most of your work has to do with food and the impact of Western consumerism on Chinese culture. When was the first time for you to eat Western food? Was it McDonald’s or Pizza Hut?

W: McDonald. I ate at the first McDonald’s in China. Someone treated me for a hamburger in 1994. We spent four hours there. The service was excellent. The place was enormous. A waiter brought food to our table and cleaned up after us. It was luxury and elegant. When I had my first McDonald’s in London in 1997, I could not believe my experience: it was cheap and uncharacteristic. The place was just a hole in the wall across street from a sewage maintenance facility. Workers came in for their break, still in their dirty uniforms. I left after only a few minutes feeling cheated. The contrast was so profound that I had to make a work about it.

S: Was it your first time abroad? What was your first impression of the “West”?W: The West in my mind, before I first went abroad in 1997, was material-driven and money-thirsty. I went to London alone. I had a map of London but it was in Chinese with pictures of subways and museums. Naturally the map didn’t help. I pointed at my map to police officers on the street. They would walk me all the way until about 10 or 20 meters to the address that I was looking for. Sometimes they would walk with me as far as a kilometer. To avoid making me feel embarrassed, they always left a few meters for me to walk on my own. The officers were so nice and considerate. At first, I was intimidated, because you wouldn’t see police carrying weapons in China. I dared not to ask them for directions. But they always approached me voluntarily. I thought to myself: “My god, is it really capitalism? It’s even better than communism.”

S: You have made a lot of reference to art history, Western and Chinese. Do you intentionally incorporate art history in your art?

W: Masterpieces are like stage props for me. Masterpieces are too popular and too well received to provoke controversy. They function, in my work, as a helper for composition. They are so familiar to the viewer that they have become part of our subconsciousness.

S: In 2006, you didn’t produce any work, but you did work on an elaborated and installation-based photograph titled Blood of the World, in which you referenced many masters’ paintings, from Delacroix to Goya. Could you tell us what the work was intended to be and why the films were confiscated? Have you had a lot of problems with permits and security? What kind of impact did this incident have on you?

W: 2005 had so many war-related memorial events: it was the 60th anniversary of the surrender of Japan and the end of World War II in Europe. I planned to shoot a photo to commemorate those events. The production was very intense. I spent over a month in 2006 in the studio to prepare the set. It would have been the most complex shoot for me. An extra actor told the police on me about the nude models. It had never been a big deal for me to shoot nudity. This incident changed my perception of artists’ freedom in China. Censorship had never occurred to me until then. I realized that there were boundaries and limits in this society. To survive, I need to put my tail between my legs. I must be humble. I can’t just think about myself and my art. I have children and a family now. Censorship could also affect them.

S: It has been 15 years since you began using photography as your primary medium. When you look back in your career, do you think your work has changed? In 2008, you employed new media: video and sculpture. The sensibility in the work is more reflective than reactive. Even in your photography, your interest has seemed to shift to the psychoanalytical impact of changes in China. If we compare Competition from 2004 with Debacle from 2009, we can see the frenzy action depicted in Competition, but Debacle is quiet and without one single person in it. It presents an almost abstract pattern with an eerie feeling of defeat and desertion. How did the transformation begin?

W: I wanted to revisit Competition, but I didn’t want to repeat. In 2004, the global economy was booming. Many Western investors came to China to open factories. But in 2009, when the economy plunged, many manufactories in the coastal areas were shut down. The world changes so drastically and so rapidly, so do people. I often think about revisiting Night Revels too, perhaps to make a video work.

I have changed psychologically and emotionally. Before my attitude was very blunt and unapologetic. Now I don’t see things black-and-white any more. I still question many things, however I am no longer so direct. Society has become so complicated. And I have become older now. I’m more cautious. I am now willing to look at various possible answers.

S: The style in your newer photographs, such as Romeo and Juliet or Safe Milk is quite different from your previous work. Professional fashion models are employed. The photos are sleek and stylish. Why did you abandon using Chinese models with awkward bodies and mundane expressions?

W: I wanted to test out a new idea to use foreigners or different models to reflect China’s new reality. I entered a group show with those photos. Many people did not recognize them at first. But I think, like my speech pattern, no matter what subject matter or what kind of models I use, I always carry my own accent.

S: You won’t go back to using Chinese models?

W: I don’t think so at least for now. I’m in the process of exploring new possibilities. I want to go to Los Angeles to do a project. In a foreign country, I want to collaborate with foreign models.

S: Your previous work addressed the polarization between the rich and the poor and the tension between Chinese tradition and Western culture. What about now? What does your work focus on?

W: Social conflicts no longer affect me as strongly as before. I was easily provoked by what happened around me when I was young. Now I contemplate more and reflect more, which slows down my work pace. It takes longer to decide on a subject matter and how to approach it. Last year in 2010, I was only able to create two pieces of work.

S: How did you like your first solo exhibition in the US at ICP?

W: They proposed to me almost five years ago. Originally I was asked to provide enough works to occupy the entire ICP space: upstairs and downstairs. I was also asked to do projects at other possible venues: Asia Society and New Museum were both mentioned. Not long before the opening, I was told that the exhibition was only going to occupy a portion of downstairs with only 15 pieces . The catalogue was canceled as well. I was disappointed and nervous. However I was wonderfully surprised at the opening, because almost 2,000 people showed up to see my work. All the curators, collectors, critics, journalists and gallerists came. They all took my work seriously. I was happy and satisfied with the job that ICP did. I realize now that the scale of the exhibition and a catalog are not as important as having people see my work.

S: Have you read all the reviews in the Western media? What do you think? Do you think their writing reflects what your work is about?

W: I don’t think it matters. It’s great to have a different point of view, even if it is not what I intended to be. It creates legend and mystery. I like it!

S: You stated that Chinese art was the center of the international attention, because of the Olympics and the World Expo. Now Beijing Olympics and Shanghai World Expo are in the past, what is your thought on the future of Chinese art?

W: The Chinese art market was full of bubbles before, but the bubbles won’t disappear so easily. The art system in the West tends to predict what’s the next or what the rules are. How can you set rules? Art is meant to push the envelope. Chinese art has a different vitality and dynamic. It’s more spontaneous. There has not been an international super star coming from China yet. Ai Weiwei could very likely become one. I think that he is a greater artist than many others.

S: What are you going to do next? Is your new studio in Song Zhuang ready for you to move in?

W: Almost. I will spend sometime getting to know the new studio space before I begin producing work. Hopefully I can create four or five pieces this year. And next year I’ll concentrate on only one piece. I am not interested in market or even exhibitions any more. I want to plan what I want to do in 10 years: a real long-term plan.

(1) As part of the New Wave, many experimental and avant-garde exhibitions were held in Hubei, such as Hubei Invitational Exhibition of New Chinese Ink Painting in 1985 and Hubei Art Festival of Young Artists in 1986.

(2) During the ’85 New Wave, they were widely called “two journals and one newspaper.”

(3) Han Xizai was the protagonist of the painting Night Revels of Han Xizai by Gu Hongzhong (937-975). The narrative painting includes five extravagant entertainment scenes at Han’s house. Han, a talented artist and intellectual, indulged himself with excessive revelry to escape his feeling of powerlessness and frustration towards politics.

(4) Le Petit Communiste (1990), with Christophe as the model.

Wang Qingsong, contemporary Chinese photographer

Jing Daily Exclusive Interview, January 28th, 2011

Last week, the artist Wang Qingsong, one of China’s top contemporary photographers,had a very busy week in New York. Launching his first New York solo exhibition, “When World Collide” at the International Center of Photography and taking part in an Art Salon at the China Institute, Wang received a warm welcome during a very China-centric week in which Chinese artists Hai Bo and Cui Xiuwenwere respectively feted at Pace/MacGill and Eli Klein Fine Arts. Prior to the opening of “When Worlds Collide,” the Jing Daily team sat down with Wang to discuss his recent work, his new exhibition, and his future plans. Conducted in Mandarin, our interview shed light into the societal changes shaping Wang’s work, his thoughts on younger artists, and his observations on the Chinese art market as it climbs back towards a “second boom.”

Jing Daily (JD): Your artwork is often focused on describing and critiquing “Today’s China,” looking at commercial wealth and consumption, as well as the migration towards cities. How do you define Chinese consumer culture? Has it evolved since you first began your work?

Wang Qingsong (WQS): China is a big consumer market. My work is not really critical towards “China today,” but rather takes a skeptical attitude toward exaggerated consumption. A lot of things are not actually that good, but their worth is amplified by propaganda, and people believe that they must have these things in order to reflect their social identities. This kind of logic has caused a lot of exaggerated consumption and blind waste. Early on, my work reflected more on China’s national culture, and changes in the modern cultural context.

JD: How do you see this theme manifesting in Chinese culture these days, and what impact is it having on your work?

WQS: At the beginning, I thought this cultural change was happening because of our intentions to improve our lives, but I gradually realized that the invasion of new Western culture was changing our values as well. This kind of change had a big influence on my work. However, the change does not only affect me, but it also impacts all Chinese people. Perhaps many years ago, people would treat this kind of culture negatively, but they got used to it later. We can boil down this change in attitude to China’s basic national policy, basically, economic development.

JD: How would you characterize the art scene in China in 2011? How has it changed over the past five years? What has improved? What hasn’t?

WQS: From 2005 up to the economic crisis, China’s art scene developed too quickly. During that period, many things weren’t thoroughly thought out, due to the rapid growth. Many works had to be done repeatedly because of the large volume of market demand. At that time, many artists were very productive. Now, the market has eased a little, and people will look at Chinese art more calmly. Artists should also think more rationally about their work. Since last year, I have not produced much new work, probably only two pieces. I started to think more about my work. Thinking is more important than doing.

JD: And how do you see your own position in the Chinese art scene today? Do you see yourself as someone who is part of the establishment? Critiquing the system as an outsider? An educator for new generations of artists?

WQS: I don’t think I am very successful. In fact, I mostly hear about it from other people. The first time I discovered that I was somewhat famous was in 1999. At that time, I went home to see my sick mother. I first arrived in Wuhan, but the train was late, so I had to spend a night there. Then I called a friend who I’d only met once before, and he arranged a car to pick me up and a decent hotel for me to stay in. He also asked some of his artist friends to come meet me. As it turned out, those people who came to meet me that night were artists I admired a lot. Also, before that point, I’d never stayed in such a nice hotel. I asked my friend why he treated me so well, and he told me that I was already famous at that point. Another time, I went to Germany. I was a friend over there who told me that I was very well-known in Germany. In fact, many times, you don’t even know that you’re famous. During that period, it wasn’t only me who doubted it. Even my mother did not believe that I was famous, and she thought I was lying when I told her that I was about to go abroad. I think we should not put ourselves in a position of feeling successful. We have to stop and reflect when we feel good about ourselves, so we can go further and do more meaningful work in our fields. I think the art system should develop slowly, as China’s economy needs to slow down. If it develops too fast, people may not absorb things correctly, and it could bring negative influences into the system as a whole. Therefore, everyone in this system needs to constantly look back, or take a break and really think about their next step. In terms of nurturing emerging artists in China, I feel it’s a tough question. In terms of art education, the Chinese system has kept a hereditary tradition, more or less, even decades after the establishment of the PRC. A veteran artist, for example, may want his or her art philosophy to be inherited by his or her students. Also, different art regions often form different factions, while these factions may have very little communication among each other. It is difficult for individuals to disrupt the system in a short amount of time. I give lectures sometimes, but these talks are all extra-curricular activities, and have little impact on the education system.

JD: In your earlier work, non-Chinese (Westerners) show up only incidentally, if at all. Yet in your newer work they have a more central position. Can you tell us a little about how these individuals fit into your work, thematically or metaphorically?

WQS: When you constantly look at one thing, you may want to turn to something fresh. One time, at an exhibition in South Korea, a friend of mine told me that he was not able to find my work as all the characters in the pieces were foreigners. In fact, he had never seen Westerners appear in my work in the past. I think this kind of otherness is very important, both for me and for the audience. I like to put different things together because this would transmit new feelings and emotions to me. However, in order to find the best balance, this “strangeness” requires constant adjustments.

JD: From your perspective, has the role of the collector in the Chinese art scene changed in the past five years? What are the contributing factors?

WQS: I think the role of collectors has been exaggerated recently. Although the role of collectors should be positive, some domestic collectors may need to improve their roles. The collector community also needs more communication. I think the culture of collecting cannot be too commercialized. The auction market in China, for example, emerged from many so-called “dark horses” last year. Some artists may have not created any work for 20 years, but suddenly they created a new piece, and the work went sky-high because of market speculation. I am not comfortable of making friends with this kind of marketer.

JD: And how about the role of museums and galleries, art fairs, and auction houses?

WQS: I believe that museums, art galleries, art fairs and auction houses are eager to do their best, but it is not easy. Some museums, for example, open an exhibition for only three or four days at a time, and the longest is half a month. Except for the opening ceremony and holidays, there is little time for people to visit, and the number of visitors is not enough. Sometimes, you may feel the exhibition is just something to go on your résumé. It is rare to see an exhibition lasting several months, like my [new] exhibition here at ICP and my former exhibition in Germany. The longer the exhibition lasts, the more chances you have to communicate with your audience. The exhibition should not just be a brief opening ceremony and a delicate album. Art museums in China need more time to adjust and calm down. I think auction houses play a bigger role than before. Before 2005, curators played a more important role. Some curators try to organize as many exhibitions as possible in order to cater to market demands. I believe it was hard for them to digest every single exhibition thoroughly. Since 2005, the role of curators has gradually faded, and the role of auction houses has increased. Auction houses have great eyes. At the same time, the influx of capital has had an effect, as some institutions started to invest in China’s booming art market. I think this kind of capital infusion has both positive and passive effects. Last year, for example, an artist exhibited 16 works in Shanghai, and in the end all these works were sold out, just like stocks. Now the art market [in China] is just like the stock exchange, and the effect of all this money coming in is even bigger than that of the stock market. A single piece of artwork might be owned by thousands of investors. I think this kind of art market may have certain risks, more or less.

JD: Do you find that younger Chinese photographers are taking a fundamentally different approach to their work than you and your contemporaries?

WQS: Now, the use of digital technology in photography is very common. Recently, there was an exhibition called “A Decade Long Exposure” celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Department of Photography at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. In that exhibition, there was a unit which included artwork from outstanding students who had graduated over the past ten years. I was surprised to see that 99 percent of these works used digital technology. I think today’s young people rely too much on digital technology. Too much reliance on digital manipulation is not good, because the image is device controlled and a similar work made by a computer would look pretty much the same. If you like a style, for example, you may want to use two or more computers to produce a piece. It ends up looking like a company’s mass produced products. In many cases, a piece of work can be replicated many times over, which ends up just looking like an advertisement. Digital technologies change rapidly, meaning that you can never catch up the speed of changes. For example, early in my career, I spent two days to make the “Thousand-Hand Bodhisattva” using digital technology, with the help of a friend. Now, with the latest technology on the market, it takes a computer only about half an hour to do the same work. The processing speed of computers is much faster than before. Also, the price of using digital technology is much cheaper. As a result, people’s artistic skills are actually inferior to computer technology. Maybe you can create very complex work now, but this work might look like child’s play after a few years, as technology is upgraded. Don’t rely too much on digital technology unless you have a really deep knowledge about it. Regarding to my new exhibition, “When Worlds Collide,” which encapsulates a decade of work, if all of my work was made with digital technology, I think the educational aspect of the exhibition would fail, because it would deviate too much from the nature of photography. Photography has its own advantages which do not always emphasize digital elements. Digital technology is merely a tool, and one cannot be too obsessed by it.

JD: Are there any emerging Chinese artists or photographers you’re keeping an eye on?

WQS: It is hard to say, because there are too many art spaces now. A new artist or photographer who just emerged would be quickly snapped up by exhibition spaces. This artist or photographer may feel some sense of success because he or she already has a market. Unlike in the past, when it was not easy for some artists to sell their work, so they had to continue to create new work and hold new exhibitions. I think artists need to constantly be suspicious of themselves and adjust their status, putting themselves in a position of feeling “unsuccessful.” Now, some students who have not yet graduated are represented by art galleries. If a person gets many good opportunities just after graduation, I think this might not be a good for his or her future career development. A person may simply be too young to fully grasp the opportunity. I myself had no good opportunities for several years after I graduated. In this regard, I think Ai Weiwei is a good example. Ai Weiwei had nothing to do when he just graduated. Suddenly, when the opportunity came, he would never give up a chance, no matter how large or small. Many good artists could not have good opportunities at the beginning. When an opportunity comes, they can unleash all of their accumulated energy out, and find great success. We cannot merely owe one’s success to chance. One’s success has a great deal to do with his or her accumulated experience and efforts. For me, I also need to accumulate experience and make adjustments to achieve my “optimal state” as an artist.

JD: What would you say is your “optimal status”?

WQS: It is a state in which “nothing matters.” I can create whatever I want. I can do whatever I want. I think this is the goal.

JD: Could you give us a brief description of “The History of Monuments,” the enormously long photographic frieze you completed last year? What prompted you to undertake such an ambitious and complicated work?

WQS: “The History of Monuments” was first shown in the “A Decade Long Exposure” at CAFA in Beijing. Before creating this work, I was curious about the maximum length a picture could be produced on one a roll of film. I found out that a roll of Kodak film can print a picture 42 meters long at the most, so I started to make this work, which is also 42 meter long. The purpose of this piece is to summarize culture. In China, people always like to sum things up in the form of a frieze, such as the summary of a year, five years, or ten years. I want to summarize certain aspects of culture in my work, although this kind of culture might not be “appropriate” by some people’s standards. “The History of Monuments” will be displayed in France this year.

JD: Is there anything more you would like our readers to know? Do you have any plans for yourself in the near future?

WQS: I think the Chinese contemporary art scene will certainly be good, because we have a huge population of 1.3 billion people, and their needs for life, as well as their artistic needs, will have a huge impact on the world. No matter whether the impact is good or bad, it is worth of paying attention to. In addition to photography, I hope I am able to extend my work to some other art fields in the future, such as TV or film. I think at a certain point, one may have some new ideas and need some new input.

JD: Thank you for participating in our interview. Congratulations on the opening of your new exhibition, and we look forward to your lecture at the China Institute tomorrow night